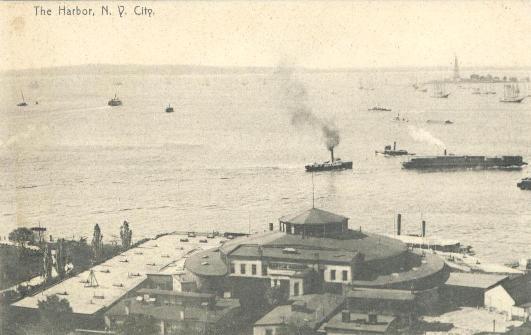

All of our Schmidt ancestors who immigrated to America from Machtlos, Germany and the surrounding villages arrived at a time before the Ellis Island immigration center existed, a time before the Statue of Liberty had been installed on Liberty Island, and (for a handful of the earlier Schmidt immigrants) a time before immigrants coming into the United States were even processed by any government authority at all. For those Schmidt ancestors of ours who arrived before August of 1855, they simply walked off the ship and strolled into America, no questions asked. For those many Schmidt ancestors of ours who arrived in the New York harbor before 1891, they were processed not through Ellis Island but rather through Castle Garden–a War of 1812-era military fortification that had been converted into an immigrant processing center in 1855.

In the article below, which was printed in the New York Times “marine intelligence” column on 23 December 1866, an English immigrant describes his observations and experience coming in to the United States of America through Castle Garden. This would have been quite similar to the experience of our earlier Schmidt ancestors who arrived via New York. Many of the immigrants that the following writer describes were destitute Irish families who were escaping their homeland as a last ditch effort at survival from the recurring famines and diseases. These Irish immigrants sometimes came to the New World with little to no planning, and would have to find jobs and lodging once they arrived. Our Schmidt ancestors, however (especially our later immigrant Schmidt ancestors in the 1860s-1880s) already had established clusters of family inside the United States, with work and living arrangements already prepared for the new immigrants. Thus, our immigrant Schmidt ancestors probably did not stay long at Castle Garden. Still, the sights, sounds, smells, and experiences that the writer describes below paint a picture that was very vivid to our immigrant forebears.

Enjoy:

The daybreak of a bright Autumn morning beamed over the magnificent Bay of New-York City as the ship Scotland, conveying some 300 emigrants from the Old World, fired a salute and cast anchor …, amid the ringing cheers of passengers and crew. It was right pleasant — after a passage somewhat protracted, but, for the season of the year, unprecedentedly propitious — to at length enter the haven where we would be. With the exception of two or three nights of turbulent weather and hyperborean blasts as she passed the Banks of Newfoundland, where many a noble ship has met her fate, the voyage of The Scotland was a most favorable one and for days and days we floated over the Atlantic on a sea so level and under a sky so calm that a pleasure yacht might have sailed over it in safety. It was indeed exhilarating, after days and nights of endurance in cabin and on deck, with the ever-same boundless blue and green of firmament and sea, with only now and then a ship in sight, or the wild wheeling sea-gull on the vessel’s track, to come in view of something like land and the great City of the world’s commonwealth, New York.

It was a sunrise in the New World! and a glorious and electrifying sight it was, as the sun, about to ascend the horizon, flooded cloud, sky, bay and seaboard, shipping and the surrounding scenery with streaks of gold and purple – the great City itself, and its sister cities of Brooklyn and New-Jersey, waking up as it were at some celestial summons out of the dreamy darkness of the night.

“Fair was the day, in short, earth, sea and sky beamed like a bright-eyed face that laughs out openly.” The steamtug … having come alongside, was engaged for a considerable time in transhipping the luggage, till at length we were safely landed on the threshold of Castle Garden, glad and grateful to set foot on the terra firma of the free, and rest our weary limbs and sea-worm souls and systems under the wing and welcome of its refuge. Here again at the landing stage, during the process of the second transhipment, a further opportunity was presented of viewing the river scenery, now diversified with its swift-moving, mansion-looking steamers, which fairly astonished the weak eyes and nerves of those accustomed only to the lilliputian streams and petit maitre miniature landscapes of England and Europe. Truly the approach to New York is one of the most splendid and imposing in the world. Talk about the approach by the Thames to London Bridge, by the Mersey to Liverpool, by the Seine to Paris, or the Lagune to Venice! Why, you might as well compare the aforesaid muddy Thames to the great father of waters, the Mississippi, or British Snowden and the Malvern Hills to the Rocky Mountains. Things European dwindle, as it were, into specks and points infinitesimal before these stupendous stretchings and these bold outspreadings. It is Hyperion to Satyr, a wash hand-basin to a bay, and never do you so completely realize the old schoolboy reminiscence. Sic parvis componere magna solbam. As it always happens when the attention is absorbed, or the mind rapt in admiration, something extraneous steps in to mar the meditation, just as on some Summer evening when the landscape is a all lovely and serene some grasshopper of bull-frog disturbs the quietude, so illustrating the potent truth of but “one step from the sublime to the ridiculous”. A bystander, in a strong Hibernian brogue, volunteers the erudite observation, “Arrah, Pat, and what do you think of Dublin Bay after that,” while another from Cockney Land apostrophizes a companion, and asks him what about the breadth of Old Father Thames at Putney. We had seen multitudes of churches, public buildings, factories, stores, and other structures, as we steamed up the Bay, but the one we had now arrived at, Castle Garden, attracted particular attention, principally, in all probability, from its being the emigrants’ destination. The eye of a military man would have singled it out first and foremost as a structure pertaining to his profession, while the eye of a civilian or of an ordinary observer would have taken it for a huge reservoir or gas-holder. The landing stage is all alive with the officers of the Emigration Commissioners and the Custom-house, and while they are engaged in their duties, the more curious are all on the qui vive to ascertain what can be the nature and object of the structure before them. Although appropriated to the purposes of an emigrant depot, it turns out to be an old fortress or castle, and remains one of the great landmarks or trophies in that eternally memorable struggle — the first great war of independence. It was built by the British in 1812, after the model of the Martello towers of the old country, when they entertained the fond but futile hope of colonizing, or, in the language (Heaven save the mark) of modern diplomacy, “annexing” America to Great Britain, and has stood dismantled and in memoriam ever since. The building is of red granite, of tremendous thickness, circular in form, and furnished with portholes and platforms, so that it is available at any moment for the defence of the harbor, only requiring a garrison and a few grim Dahlgrens to impart to it its real character.

Truly strange and checkered is the history of this structure. After the first war, and when the peace and prosperity of the City were in their zenith, the building was converted into a saloon for the amusement of the people, and has on occasions held as many as 4,000 people, when JENNY LIND, the Swedish Nightingale, and MARIO and GRISI electrified with their melody the musical elite of New-York. Here also JULLIEN wielded his magic and memorable baton before thousands at his promenade concert. The building has also since been devoted to religious services and the meetings of mechanic’ institutions. Although the saying of SHAKESPEARE be trite, yet the ever freshness of it is a truism, both to men and things — “To what strange uses do we come at last!” — is curiously applicable in this case, for now more marvelous still we have the structure devoted to one of the noblest of humanitarian uses, that of a depot, established by a paternal Republic for the strangers and children of other lands who seek its shores in such undiminished shoals.

All being ready, the emigrants proceed in a body up the corridor into the interior of the building, their boxes and baggage being removed to the luggage warehouses, and here they range themselves in order on the seats. In front of them, and in the centre of the building, which is lit by a glass dome, stand a staff of some dozen gentlemen, all busily engaged in making arrangements for facilitating the movements and promoting the settlement of the newly-arrived emigrants. Each emigrant, man, woman and child, passes up in rotation to the Bureau, and gives to the registrar his or her name and destination, as a check upon the return of the Captain of the vessel, who gives the name, place of birth, age and occupation. One of the leading officers connected with the Bureau of Information then mounts a rostrum, and addressing the assembled emigrants, tells them that such as are not otherwise provided for, or prepared to pay for their accommodation, can find shelter under the roof of that building; that advice and information of the best and most reliable kind can be had relative to tickets for railway and steamer to take them East, West, North or South; as to the best means of obtaining employment, for which a register is kept in the Intelligence Department of the Institution; also as to the best and most expeditious routes to take, with facilities for corresponding with friends, and of changing money at the Bureau of Exchange. The Intelligence Department is largely resorted to by emigrants, inasmuch as there they can obtain information as to probable situations without fee, for which outside they are asked $2 by the employment agents. A careful supervision is exercised by the office as to the suitability and respectability of the parties on both sides. All this is well and wisely done for the protection of the emigrant, who would otherwise, if let to himself, become the prey of sharpers, boarding-house “runners”, “scalpers”, leafers, et id genus omne. Such as are ill or invalid are at once sent to the State Hospital, where they receive the best of medical treatment and general attention. A tolerable estimate may be formed of the work and labor devolving on the establishment, when it is remembered that during the past month of November, 17,280 emigrants had arrived at Castle Garden, or a grand total of 219,830 to that date since the beginning of the year, while according to the latest return made up to Thursday last, the total number of arrivals from January to Dec. 5, had reached the enormous number of 222,494, being an increase of 26,142 over the corresponding period of the preceding year–all permeating and passing through the great artery of life and labor at Castle Garden. The advantages conferred by the regulations of the institution are developed every day in the shield of protection that, by means of its advice, information and police, it confers on the unsuspecting emigrant and on the unprotected female, the friendless, the orphan and the widow.

Such is Castle Garden as a great national refuge for the emigrant from all lands. It has nothing to parallel it on the continent of Europe. It stands alone in its noble and utilitarian character.

It was nearly evening before all the business connected with the emigrant department was over and the emigrants began to settle down in their new locality, and the building being lit up with gas gave a more cheerful aspect to the interior, and enabled us to survey the somewhat novel scene before us. You could at first imagine, were you not painfully conscious to the contrary, that all those human beings seated on the benches had assembled to witness some theatrical entertainment. On looking right and left, an arrangement will be observed to have been effected, pace the emigrants marched in miscellaneously—the Germans and Dutch, who form by far the most numerous body, being parceled off into the eastern portion of the building, which is separated from the other portion, which contains indiscriminately English, Irish, Scotch and French. Two large iron stoves, between four and five feet high, fed with plentiful supplies of anthracite, and throwing out considerable heat, occupy each end of these apartments, one being set apart for the males and the other for the females. In a far corner of each compartment is a kind of refectory, where for fifteen or twenty cents you can obtain a half a pint of coffee, a roll, cheese or butter; but many of the emigrants appeared to prefer purchasing their own tea and coffee, and preparing it in tin utensils in the stoves. There are two water taps and an iron ladle at each end of the division, from which draughts of the Croton are in constant request, nothing in the shape of wine, lager beer or spirits being allowed to be sold upon the premises. Two very civil and intelligent watchmen reconnoitre during the night to keep order and attend upon the emigrants, both having served their country in the late war. One will not very readily forget his first nights’ sojourn at Castle Garden. They were indeed “noctes noiauda”—anything but “noctes ambrosiana”—it’s hard boards anything but a bed of roses. Having determined to rough it with our traveling companions, who could not afford a dollar for their bed and breakfast, we essayed a sleep, but vainly. Somnus had no compassion on the denizens of Castle Garden, however much they may invoke him, for such is the cold comfortless, sepulchral character of the place. This, it is only fair to state, was the experience of the writer before the building had been placed in thorough repair arising from the wind whistling through the open casemates, doors and windows, combined with the tantamara of tongues, the squalling of children and the erratic ramblings round about of a colony of rats that it was impossible to obtain repose, even after a fortnight’s rocking to and fro and reeling in the Scotland, the snug hammock of which was a comparative paradise to this. Those who were unable to sleep rose and stood around the stoves.

One subject of conversation adverted to with melancholy interest had reference to the suspected murder of one of the emigrants as the Scotland was leaving Liverpool. At all advents, the body of a respectably-dressed man, with a letter in his pocket was found stowed away in one of the recesses of the engine room, some 30 feet below deck, and in a place the seamen and firemen affirm where it could not have got by accident or a fall. The supposition is that the man was first murdered on board, and then secreted below. The head and body were dreadfully mutilated. On being discovered the body was wrapped, with some fire bars in canvas and thrown overboard. We are not aware of whether any report of this mysterious affair was made to the Emigration Commissioners or to the British Consul either here or at Liverpool, but it was a matter that called for investigation, and cast a gloom over the passengers for the remainder of her voyage. Every one, through the columns of the NEW-YORK TIMES, is now familiar with the ultimate unhappy fate of the Scotland on her return voyage, the fourteenth that she had made in and out in the service of the Transatlantic Emigration and of the National Steamship Companies. But there is one interesting incident illustrative of the sagacity and fidelity of a Newfoundland dog on board the derelict vessel, the Kate Dyer, that deserves to be recorded. Just after the vessel was run down by the Scotland and about to sink, the dog was seen to rush into the water and endeavor to rescue a youth from the watery grave that awaited him. Three successive times the dog dragged the body of the boy from the sinking ship, and the third time it slipped from him; foiled in his attempt he stood for a minute or two more howling and mournfully watching the scene, until, in desperation, he made a fourth attempt to float the body, but with no greater success than before; unsuccessful in saving the life of the lad, the Captain and crew of the Scotland, who had been intently watching the efforts of the noble animal, rewarded him by saving his life and hauling him in safely on board ship amid the cheers and congratulations of the crew.

As may be imagined, much of the conversation of the sleepless emigrants that night was directed to the good or bad fortune they had met with during the day in quest of situations and employment, and many came back reporting dolefully and despondently in that respect. Bakers butchers, boiler-makers, gardeners, grooms, and in fact masters of almost every calling to be found in the book of trades, all stated how they had canvassed the various establishments in the great City during the day, and had found, with some few exceptions, that they were all full, and that no help or hands were wanted. Never were the advertisements columns of the TIMES and other papers, for “help wanted,” devoured with such avidity or the few cents for their purchase invested in them with such readiness, and it is gratifying to state that in very many instances they led to the procurement for the poor emigrant of a billet and a home. The report of a second and subsequent day’s pursuit of employment under difficulties showed a much more gratifying result. Some had been temporarily, and others conditionally, engaged, either in factories or at farm-work, the latter at $12 a month and their keep, while many who had not succeeded were kindly sent, by order of the Commissioners, to Ward’s Island, to be employed in miscellaneous work about the State Hospital and grounds, or to work at their respective trades, for which they received their board and lodging in return, until something better could be obtained for them. Most of the strong, healthy girls and young women, principally Irish, succeed, through the agency of the Labor Department of the Commissioners, in obtaining situations as housemaids, nursemaids, milliners, sewing-machine hands and dressmakers, and in a few days bid adieu to the sheltering care of Castle Garden. At one time, when matters looked very discouraging in the way of getting work, and many of the emigrants, after disposing of their wearing apparel, were reduced to their last few cents, the propriety of waiting in a body on the British Consul was mooted, but the suggestion was not carried out in that form. One or two, however, did venture in their individual capacity, to wait on that functionary, and after making a statement of their forlorn and embarrassed condition, were informed, to their great discomfiture and chagrin, that the Consul, although the representative of Great Britain for the protection and assistance of British subjects, had no power to render them relief, pecuniarily or otherwise, and that all he had the power of doing was to give assistance to seamen in shipwreck or distress. A poor Frenchman, who had been a waiter in Leicester Square, reduced to his last sous, also waited on the French Consul and was told to “go to Castle Garden.” A similar application to a Society entitled the St. George’s Society, having the reputation in England of being a good Samaritan body of gentlemen who relieved and assisted Englishmen on their arrival here, met with a similar result, it being explained by the Secretary that the limited funds at the command of the Society were appropriated to the assistance, not of emigrant Englishmen, but of needy natives and of indigent men and women far advanced in years. Well with such Job’s comforters as these, might the aid of Providence be invoked by the poor emigrant! Still, as a pleasing set-off to all this, many were the little incidents told of hospitality and charity shown by residents and natives to the newcomers in their difficulty–such as the giving them a day’s work and a dollar, or a hearty meal and information as to the best means of getting work, showing a genuine sympathy and fellow-feeling on the part of those who had once been adrift and in difficulty themselves.

Among the emigrants that came out on the Scotland, were three or four poor fellows who turned out to be “stow-aways”–that is to say, persons who had stowed themselves away clandestinely on board, anxious to get across, and willing to run the risk of doing so, even at the risk of three months hard labor. They were not discovered until the vessel neared New York, when every man was challenged for his ticket, and of course, in these cases, there being none to produce, the interlopers were detected and taken before the Captain, who at first threatened to exhibit them in irons on the quarterdeck, but relenting, on second consideration in his more serious intentions, he determined, after the administration of a few cuffs and a severe shaking from one of the mates, on making them work the remainder of their passage, and forthwith, the ship being short of hands, set them about swabbing the decks and helping the firemen in the coal bunks. And right glad were our “stowaways” of the mercy shown them, seeing that they had all along secured, and would continue to do so, food and lodging to the end of the voyage. At one time it was seriously contemplated by some of the more desponding and disappointed to turn “stowaway” and return from whence they came, in spite of being made the laughing-stock of those at home; and some half-dozen, who could not be induced “to wait a little longer,” actually went on board to return with the Scotland.

A very noticeable thing among the miscellaneous crowd was the attention paid by the Irish portion of it to their devotions. Invariably as vesper and matin time drew nigh, men and women scattered here and there were to be seen upon their knees in supplication. At least one-third of the emigrants by the Scotland were Irish, most of them vigorous, spirited young men, many of them bent on joining the Fenian brotherhood, and speaking enthusiastically of its progress. There were two or three young priests among the number. It is astonishing how the Irish take to this country, and no wonder when it is remembered how differently they are treated to what they are in the old, of which they speak with great bitterness of spirit. Many are the weeping eyes and widowed hearts, that now under the great exodus going on are leaving their native shores, and it is understood that in the Spring the number of new-comers, more particularly from the counties of Waterford, Wexford and Cork, will be enormous. They know they can find a free home in the far west, and that they will be treated with kindness — kindness that great key to good will and willingness of every man’s heart, the want of which on the part of England and the English people, not less than their political wrongs and maltreatment, has been the great secret of the inveterate and vendetta-like feeling and alienation of Ireland from the mother country. In the States, they no longer have “the country” thrown in their face, and “no Irish need apply” is never heard in dealing with Americans. There was one among the group of woman who was the object of great commiseration. She had lost her little one on the voyage, from fever, and the poor child had to be thrown overboard, she, poor mother, being left, like Rachel, weeping for her child and would not be comforted because it was no more. It is indeed a sad thing to have to hide one’s offspring in the grave on land, but there is something about death and burial in the cold canvas winding-sheet at sea, in a fathomless grave, yet harder and more galling. It is pitiable to perceive the condition of some of the young women who arrive from the mother country in the family way, though it is at the same time satisfactory to think that they will not aid in swelling the huge holocaust of infanticide there, but that their offspring, cherished and taken care of with the mothers by the State Hospital here, will form additions to the future populations. There was no prohibition against “smoking” at the Garden, his pipe being one of the prime comforts and companions of the poor immigrant in all his vicissitudes and “trials,”and the fragrant weed was freely indulged in, the more so as it was very properly prohibited, excepting on deck, during the voyage, or if indulged in, it was at the risk of being put in irons by the Captain. Two stories were told of two adventures in one of the least reputable parts of the City, not a stone’s throw from Castle Garden, which if true, or of more frequent occurrence, call for serious investigation. A mulatto man from Liverpool, going down South to the cotton plantations with which he was connected, states that on one occasion he went into one of the lager-beer saloons; and having occasion to go into the back part of the premises, through a long and dingy corridor, when at the end the gas-light was suddenly extinguished, and hearing some mysterious movements, and mindful not only of his life, but watch and money, he precipitately and successfully recovered his way back and immediately left the suspicious premises and people, from which he heartily congratulated himself on his escape. Another emigrant went, the day after his landing, into a lager-beer shop kept by an Irishman, in Washington Street, without knowing the character of the locality, had a glass of beer, and sat down to rest himself, and, being rather travel-worn and weary, after being about ten minutes in the bar unconsciously closed his eyes. Suddenly the brute of a bartender, in a rude Irish brogue, ordered him to get up and go out. Taken by surprise at the abruptness of the treatment, the poor emigrant stood and stared, when the ruffian seized a heavy wooden club in the corner, and, uttering an oprecation about the English threatened to smash his customer’s brains out, and as he slowly left the place, actually hit him a heavy blow with his club upon the shoulder. The occurrence may be left to speak for itself, and may be recommended to the notice of the Police. As a general rule, the emigrants behaved themselves throughout the voyage, with remarkable decorum, which was not even infringed upon when one fine night they held a sort of sea-carnival or dance on the after deck of the Scotland. It was pitiful to meet with some at the Garden who had to bemoan the loss of their boxes, and ludicrous on the other hand to see how one poor girl had contrived to keep all her earthly stock of goods in the fragile interior of two bandboxes.

Many were the complaints made by the poorer class of emigrants—forgetting that it all arose out of the war—at the high price of provisions—just double that in many instances they paid in the old country, and hoping that, if for their sakes only, the country would soon return to the ante-war prices—a consummation most devoutly to be wished. All appeared to be hearty and in good health, that most priceless of blessings, for “he that hath thee,” says Sterne, “has everything with thee, but he that is so wretched as to want thee wants everything with thee.” Only one or two cases had to be sent to the hospital, and altogether the vessel had a clean bill of health, far different from last year, when owing to the prevalence of cholera, many died and had to be thrown overboard. No inconsiderable amount of thieving occurred both on board and at Castle Garden, of wearing apparel and other articles and one night at the Castle one emigrant, subsequently detected through the vigilance of Officer Murphy, had the effrontery to rob another by whose side he was sleeping of his watch. In fact nothing was safe out of sight or hands for a minute from the marauders and pilferers. The crew of the Scotland being short-handed many of the emigrants were well cared for in grub and grog and paid extra for lending a hand on deck, and most lustily did they work at the ropes, singing “Yea, yeo, yea, yeo, we are all bound to go.” Many of the men had become grizzly and hirsute, and much wanted a clean shave, but almost stood aghast when they heard that it would cost them twenty-five cents to have their beards taken off–an operation that, when last effected, they only paid a penny for. I have since seen some of those emigrants who were at first so despondent and could get no work, and it was delightful to see what transformation they had undergone. They had obtained situations either in stores or in some capacity and were all happiness and smiles. Their patience and perseverance had been rewarded. One or two practical thoughts and suggestions appear to arise out of the foregoing “olla pedrida” of the experiences of an emigrant. It would be a good plan if the Commissioners, in order to facilitate and increase the opportunities of getting work, were to invite notifications wherever hands were required from establishments and factories throughout the City and State, and keep a register for the purpose. Lists might be advantageously posted up in the garden, together with the daily newspapers, for the information of the emigrants. The vast space at present unappropriated in the balconies of the building might be converted into dormitories for the women and children, and those in delicate health, and a towel or two, some soap, and other requisites, would be useful supplemental articles in the washing rooms. Many a poor emigrant comes over in a filthy and verminous condition, and the first thing done with such would be to order them a bath and send them to the hospital, where their clothes might undergo a process of purification and fumigation, and so prevent the spread in the New World of the pestilences of the old. It is true the emigrant can go to church, but a better observance of the Sabbath might be added to the other regulations and arrangements of Castle Garden. One of the officers might offer a few prayers, or read a discourse, or raise a hymn, or the chaplain of the State Hospital or other establishment in the City might officiate in the evening.

Farewell, Castle Garden! I have met with nothing on the continent of Europe that can at all compare with the spectacle thou presenteth, and the benevolence and benefits that thou bestoweth – sacred asylum of the emigrant escaped from the dead ooze and dead lock of the Old World to the new life and progress, splendor and expansiveness of the New, where, under thy paternal and excelsior system, he may be no longer subjected to the terrors of landlordism, the tyranny of taxation or the evils of class representation; but, being welcomed into the great family of freedom and becoming a loyal son of the Republic, almost realize the Arcadian representation of the poet, when he tells them to go…

“And rear new homes under trees that glow

As tho’ gems were the fruitage of every bough;

O’er the white walls to trim the vine,

And sit in its shadow at days’s decline,

And watch their herds as they range at will,

Thru’ the green savannas, all bright and still.”Again Castle Garden — benevolent vestibule to this better land, and this better state of things! Farewell…C. M. A.

Castle Garden ceased to be the main immigrant-processing center when the federal government took over that responsibility in 1890 (moving operations temporarily to the Barge Office and ultimately to Ellis Island in 1892). However, a non-profit group called the Battery Conservatory has established a website at CastleGarden.org where you can, at no cost, search for records of immigrants who came into New York via Castle Garden during the 1800s. Although many of our Schmidt ancestors immigrated to America through other ports, like Philadelphia and Baltimore, you can find some of our ancestors in the Castle Garden database, such as Georg Karl Schmidt (1864-1933), who was processed through Castle Garden in 1881 before ultimately settling in West Bend, Iowa.