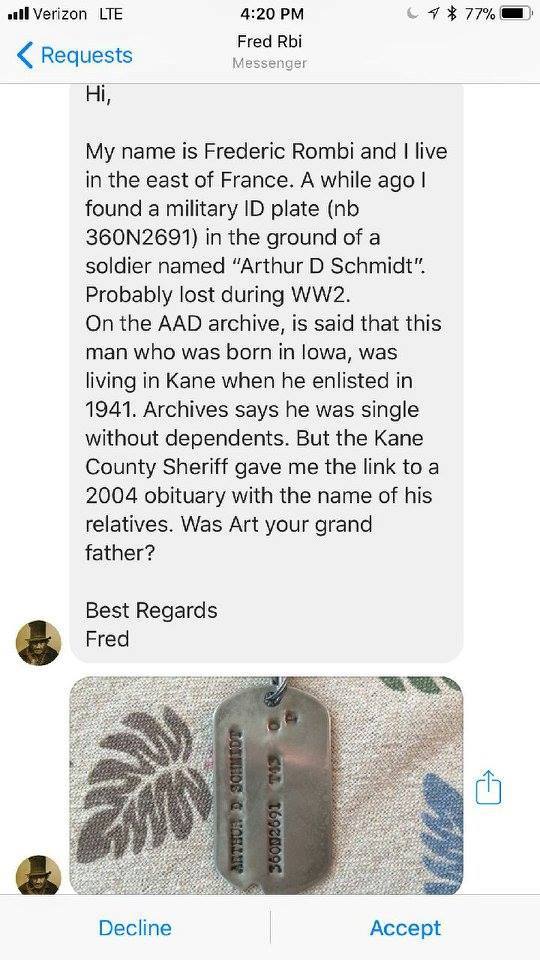

In early October, Rachel Fehr of Colorado and Anne Dahlhauser of Storm Lake, Iowa received messages from a man in France, which would connect their family history to events in Europe that took place over seventy years ago. At first, Rachel and Anne were skeptical about the authenticity of the messages, concerned it might be part of a scam. The Frenchman, named Frederic Rombi, stated that he was trying to return an American military dogtag to its rightful owner. A friend of Frederic’s had found the dogtag several years ago, and it had become a favorite key chain of Frederic’s. As it turned out, the dog tag that Frederic held had once belonged to Arthur “Art” Schmidt (1917-2004), the grandfather of Rachel and Anne, and the father of John Schmidt.

Art Schmidt’s story began on the Fred and Emma (Messner) Schmidt family farm, in the Kossuth County countryside between West Bend and Ottosen, Iowa. He was the second oldest of fifteen children. By 1940, Art and some of his oldest siblings had relocated to Elgin, Illinois to find work during the Great Depression. It was in Elgin that Art got engaged to Alma Laura Rein (1916-2000). On Monday, February 10th, 1941, as war raged in Europe, Art anticipated a possible American entry into the conflict almost a full year before Pearl Harbor. The 5’4″, 166 lb., 23-year-old man went to Chicago and enlisted as a warrant officer in the US Army. He would be joined by his brothers, Orville, Delbert, Alvin “Swede,” and Lester “Skip.”

After enlisting, Art trained at Fort Ord near Monterey, California and was subsequently stationed with the Third Infantry Division at the Presidio of Monterey. The Third Infantry Division, with its blue and white striped diagonal symbol, had a meritorious reputation from World War I, when it had become known as “the Rock of the Marne.” They were also known as the “Fr’isco Guard,” due to their proximity to San Francisco. What was originally supposed to be a 1-year commitment became an indefinite commitment when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. They were moved off base to the foothills around San Francisco, and told that their service would be required for the duration of the war, which would turn out to be about four more years.

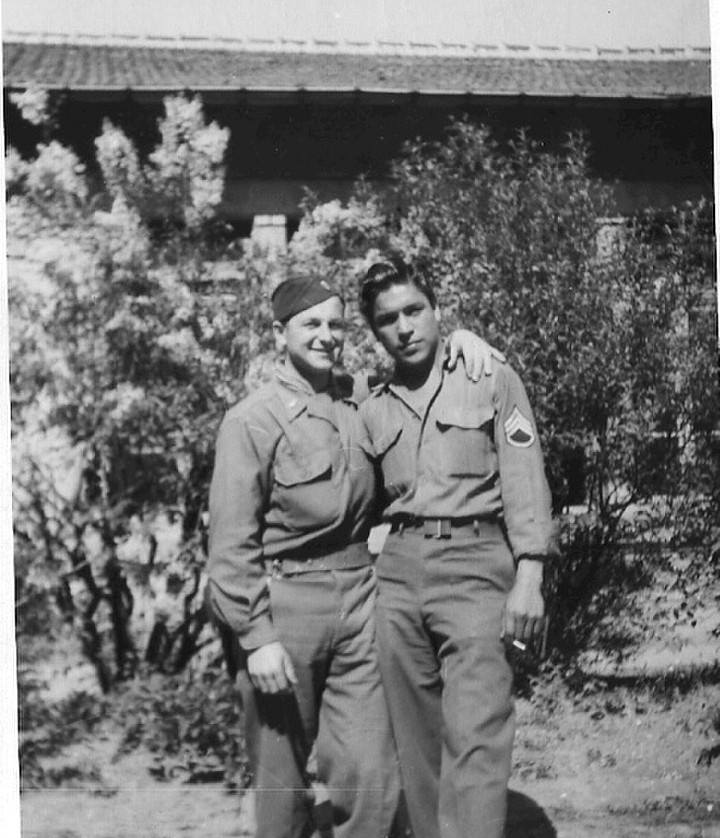

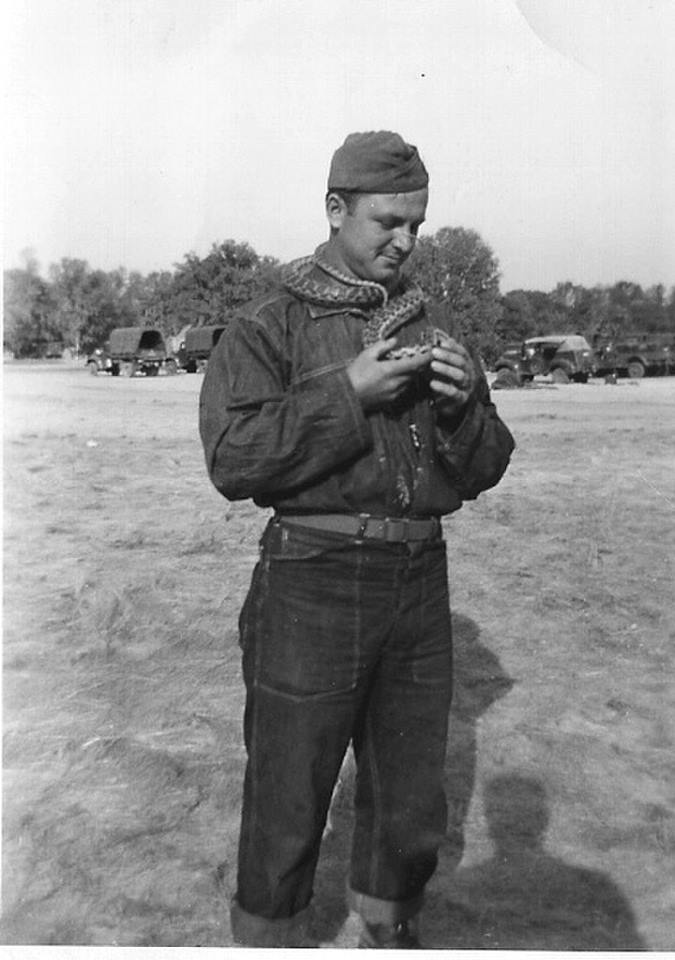

Art Schmidt and his friend, Medal of Honor recipient Lucian Adams

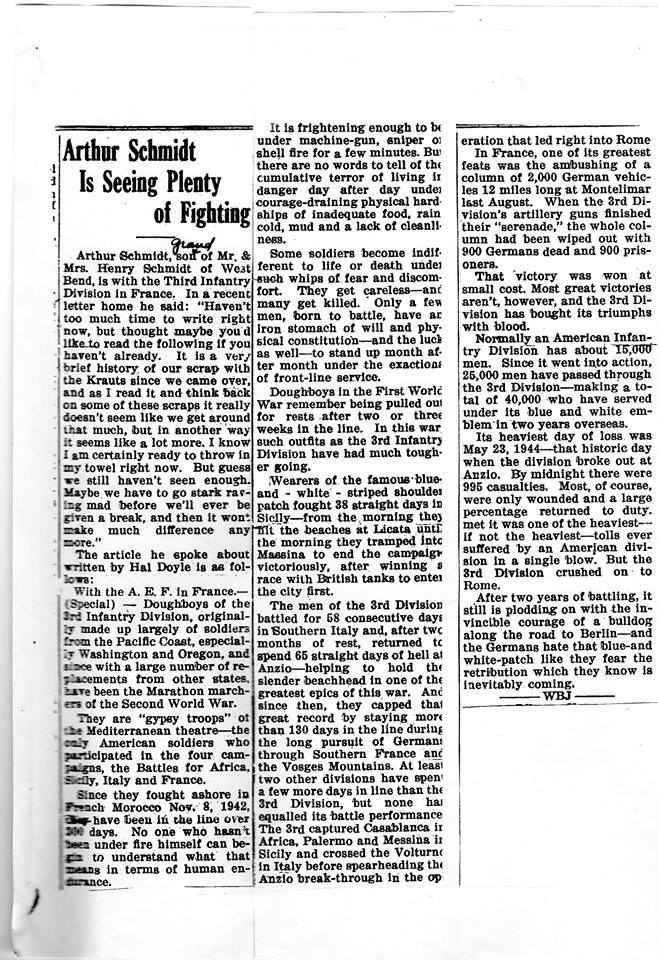

The Third Infantry Division was one of the most mobile units in World War 2, and earned the nickname, “the gypsy troops.” They were the only division in the war that fought on every single European front. While most units in World War 1 had seen front line action for two or three weeks, the Third Infantry Division were on the front line for hundreds of days, often going months without a break. The pressures of living under machine gun, sniper, and shell fire were compounded by malnutrition, cold, rain, mud, and disease. The stresses took their toll on Art, who–in 1945–wrote home saying, “I know I am certainly ready to throw in my towel right now. But guess we still haven’t seen enough. Maybe we have to go stark raving mad before we’ll ever be given a break, and then it won’t make much difference any more.”

West Bend Journal, 15 February 1945, page 1, columns 5-6

Art coped by forging lasting friendships with other troops, becoming a hand-to-hand combat instructor, and keeping a pet bull snake in his tent and shirt (the bull snake protected the men from rattlesnakes).

Art’s division fought ashore in French Morocco on November 8th, 1942 and battled their way through Africa, capturing Casablanca in the process. They won the Tunisian campaign in May of 1943, and two months later landed at the beaches of Licata, fighting 38 straight days, taking Palermo, until they marched 90 miles over 3 days into Massina to finish the campaign for Sicily. The Third proceeded to battle for 58 consecutive days in southern Italy, rested for two months, and engaged in 65 consecutive days of exceptionally bloody campaigning at Anzio. At Anzio, they succeeded in holding the pivotal beachhead, crossing the Volurno River, and clearing the way for the march into Rome.

With scarcely time to recuperate, the Third landed at St. Tropez on the French Riviera and surged northward into southern France and the Vosges Mountains. They pushed the Germans back for 130 days. Among their many noteworthy feats was the ambushing of a column of 2,000 German vehicles that resulted in 900 German prisoners and 900 German deaths. These victories were won at high costs, with over 40,000 men having passed through the Third between 1942-1944, where a division usually claimed 15,000 men.

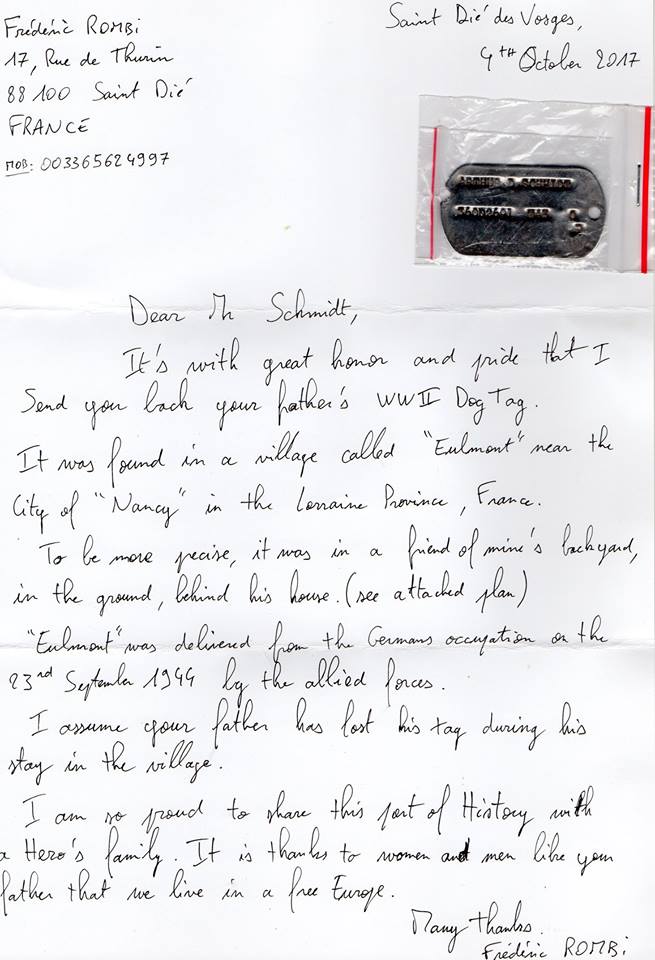

As the Americans pushed the German troops toward Germany, they liberated the village of Eulmont near Nancy, France, on September 23rd, 1944. It was here, in the midst of the fighting, that Art Schmidt dropped his dog tag and lost it in the mud behind a home.

The property in Eulmont, France, where Art Schmidt lost his dog tag in 1944

By November of 1944, the Americans arrived at the outskirts of a town in east France called Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, or St. Die for short. The town, on the banks of the Meurthe River, was an old town rich in history. It had been named after a seventh century hermitic monk, St. Deodatus of Nevers. The town, population 17,500 (1944), also contained an eleventh century cathedral, and had long been known for its lumber, weaving, hosiery, and tiling industries.

The Cathedral of St. Die, today

When the Americans neared St. Die, they noticed an eerie stillness about the town, seeing no one–not even animals–in the vicinity. Sensing a trap, they held back, continuing to survey the town from afar. In the dark night, they began to see a few German troops (actually Slavic men pressed into service of the German army) moving suspiciously around the houses. Unbeknownst to the Americans, the enemy was going from house to house and dousing the buildings in gasoline.

The location of St. Die in France

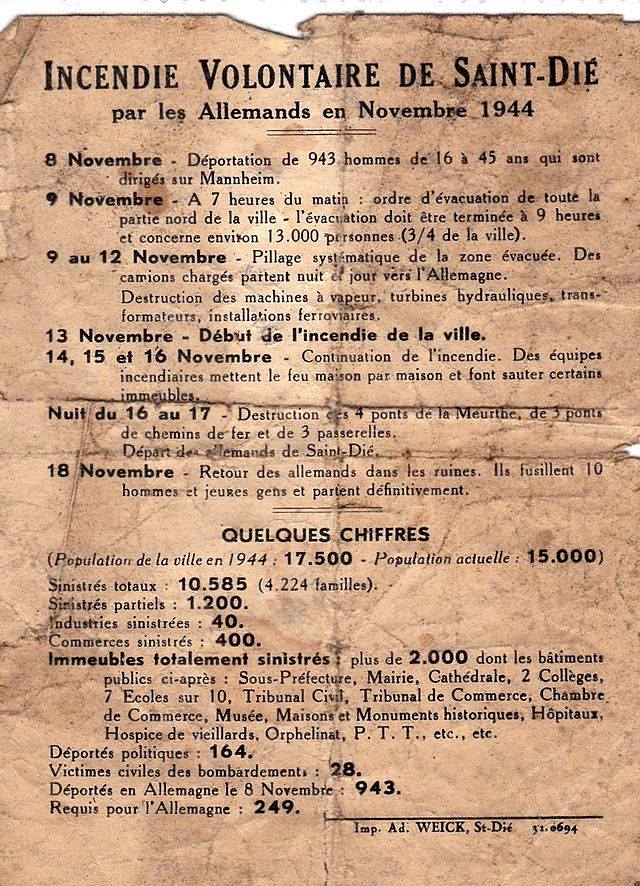

Five days earlier, the Germans had begun the evacuation of the town, deporting 943 of the 16- to 45-year-old men to Mannheim. The following morning, most of the remaining inhabitants had been expelled from the town and the houses had been looted. The next three days saw the Germans’ destruction of the infrastructure in and around the town. On the night of November 13th, the fire was lit. It spread from block to block, engulfing the town in a wall of flame that was said to have turned night into day. Over the next few days, whenever the fires would begin to wane, the Germans would return to the town to reignite them and demolish certain buildings entirely. The arson was ostensibly in retaliation for French resistance to the occupying German troops. On November 18th, the Germans returned one last time to the ruins, shooting ten survivors and departing permanently.

The destruction of St. Die, 1944

The emptying and destruction of the town entailed the deaths of 10,585 inhabitants, the complete destruction of 40 buildings and 400 businesses, the partial destruction of 1,200, and damage to over 2,000 structures. On November 23rd, 1944, the Third Infantry Division, and a handful of other divisions, entered St. Die to reestablish order and help the townspeople begin the process of rebuilding. It was here that Art Schmidt was field commissioned as a Lieutenant.

An account of the destruction toll of St. Die

A plaque commemorating the American troops’ liberation of St. Die

The Third Infantry Division continued onto the Rhine near Strasbourg a few days later, and maintained defensive positions for two months. They cleared the Colmar Pocket on January 23rd, 1945, advanced into Germany in March, and then captured the cities of Nuremberg, Augsburg, and Munich in late April. When the war ended, they had made it all the way to Salzburg. Art Schmidt returned home to Illinois in August of 1945, where he promptly married his fiancee Alma and received his honorable discharge at Fort Sheridan (in the middle of their Chicago honeymoon).

Alma and Art Schmidt’s wedding photo

About sixty years later, an inhabitant of Eulmont, France noticed Art’s dog tag embedded in the soil in the backyard of her home. The homeowner gave the dog tag to her friend, Frederic Rombi of St. Die. Frederic held onto it for several years, believing it belonged to a soldier who had gone missing in action. Curiosity got the better of Frederic, and he decided to do some investigating. He matched the identity of the dog tag’s original owner to Art Schmidt’s record in the US Archives, and then matched the US Archives record to Art’s 2004 newspaper obituary (provided by the Kane County Sheriff’s Office and the Kane County Veterans Assistance Commission) where Art’s children and grandchildren were named. “Apparently, my name was too common to track down but my girls’ names not so bad,” said Art’s son, John Schmidt.

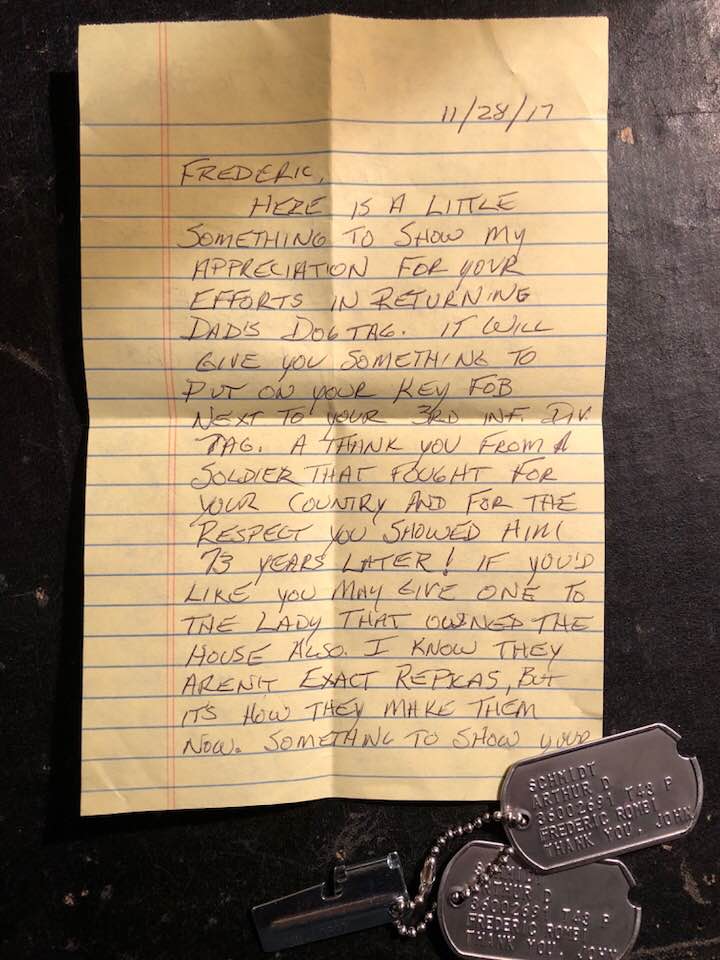

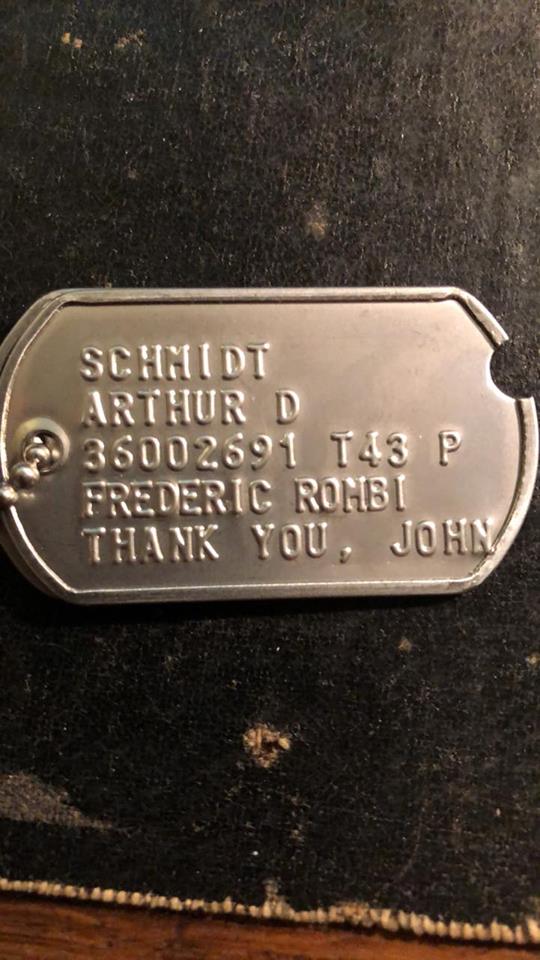

Since reaching out to the Schmidts, Frederic has become good friends and penpals with John Schmidt, who was elated to have the dog tag returned to his family. The returned dog tag was accompanied by a letter from Frederic Rombi, which stated: “It’s with great honor and pride that I send you back your father’s WWII dog tag. … I am so proud to share this part of history with a hero’s family. It is thanks to women and men like your father that we live in a free Europe.” Knowing how special the dog tag had been to Frederic, John returned the favor by having two replica dog tags made, which contained Art’s info as well as a “thank you” note from John.

In addition to the gratitude expressed by John Schmidt and his family, the Hans Schmidt Family Association also thanks Frederic Rombi of St. Die for his hard work and diligence in adding an important puzzle piece to the story of the Schmidt clan.

See news reports on this story:

- World War II Veteran’s Lost Dog Tag Returned To Family In Iowa – CBS Chicago

- Social Media, Kane County Connect Family to World War II Dog Tags – Aurora Beacon

- Kane Veterans Office Helps Return Soldier’s Dog Tag After 70 Years – Kane County Connects

- A Soldier’s Dog Tag Comes Home After 70+ years – Storm Lake Pilot Tribune

CREDITS: Schmidt family photos are courtesy of John Schmidt; French photos are courtesy of Frederic Rombi; maps and street views are from Google Maps. Information about Art Schmidt was provided by John Schmidt.

Great job Josiah! Incredibly interesting read! I had no idea uncle art was a war hero. I only knew him as soft-hearted teddy-bear!!

Very nice job. I had misplaced my copy of John Schmidt’s letter with the lost dog tag story. Googling brought me here and you gave me more information than I could ever hope for. Thank you!